Although I’m not a novelist or a poet, in my humble Substack newsletter I’m following in a long tradition of women writing. How long? We don’t know exactly, but women have been writing for as long as people have been writing. In fact, women have often been at the forefront of writing.

We can’t know for sure who did the first writing. Plus, writing seems to have developed in phases, starting with symbols and proceeding to the actual recording of spoken language, so it’s hard to pinpoint what the first writing was — let alone who was doing it.

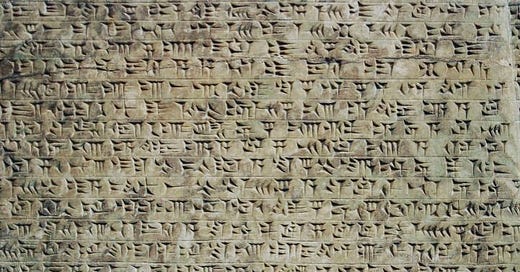

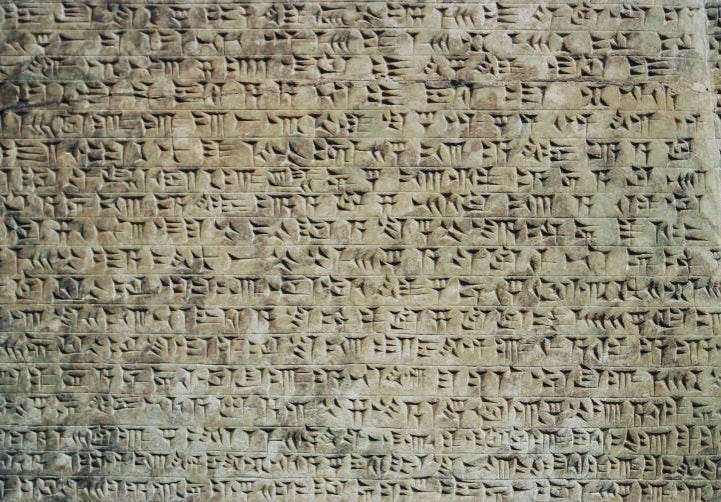

But the first literary, non-anonymous author who’s been found so far was a woman, a priestess named Enheduanna. She wrote narrative poems, some political and some religious, in the city of Ur — a Mesopotamian city in what’s now Iraq — around 2300 BCE.

Like much of women’s history, this finding has been doubted, minimized, and ignored. Back in 1927, archeologists excavating Ur discovered clay tablets containing Enheduanna’s work in the ruins of a temple. As with most such discoveries, there were questions, but some of them seem — well, a bit odd. When a statue was found at the site depicting a woman with a tablet in her lap, Elizabeth Winkler reports in the New Yorker, a male scholar had this to say: “Our specimen carries a tablet on her knees. Its meaning is not clear to me.” Hmm … the fact that ancient Mesopotamians wrote on clay tablets couldn’t possibly mean that the statue represented a woman reading or writing! Other scholars simply dismissed or otherwise minimized the discovery — one referring to the temple, which he himself was certain had served as a school, as a “nunnery” and a “harem.”

Doubts remain about Enheduanna to this day. But the point is not to insist that the first literary writing must have been done by a woman. The point is to entertain the possibility that it might have been. The point is to stop ignoring evidence because we think all the interesting and important things must have been done, or at least started, by men. The point is to record and teach all history, including women’s.

Even though she was discovered nearly 100 years ago, in plenty of time for her to be included in my education, I only learned about Enheduanna this past November when I read the New Yorker article. Many people haven’t heard of her. Nor have they heard of Christine de Pizan, the medieval writer I wrote about a couple weeks ago. Neither of these women were obscure during their own time, but they’ve been nearly erased from our time.

What other women writers did we miss?

Women all over the world must have been writing early on, though finding records of them is tricky. A few notable ones are documented. I hadn’t heard of Ban Zhao, a Chinese poet, writer, and historian born in 45 CE, but she was well known and influential in her time. We have quite a bit of evidence that English women were writing extensively as early as 650 CE, well before Christine de Pizan. Many of their works, though, were lost, suppressed, or even destroyed. Women dominated literature in Japan during the Heian period (794–1185 CE) — including Murasaki Shikibu, who wrote The Tale of Genji, considered to be the world’s first novel.

Women were often the ones writing novels, and they were often forgotten. It wasn’t till after college that I read Mothers of the Novel: 100 Good Women Writers Before Jane Austen and some of the books in the companion series released in the late 1980s by Pandora Press. Jane Austen is perfection, so it’s not surprising that the writers in the series weren’t as excellent as she was. But it was thrilling to find so many really good ones that came before and informed her — to be reading some of the same writers that she was reading and referring to in her own novels. Some of them were literary celebrities in their time: Aphra Behn, who doubled as a spy, Fanny Burney, who may have inspired the title of Pride and Prejudice, and Maria Edgeworth, whose writing defied social norms.

Although so many women writers influenced Jane Austen and the novel in general, their names fell by the wayside and their role in developing the novel was ignored by critics. Neither novels nor their writers were highly regarded in Austen’s time; some of her characters compare novels, many written by women, unfavorably to “loftier” works, often written by men. Austen felt she had to defend the novel, as she does so eloquently in Northanger Abbey:

“It is only a novel ... or, in short, only some work in which the greatest powers of the mind are displayed, in which the most thorough knowledge of human nature, the happiest delineation of its varieties, the liveliest effusions of wit and humour, are conveyed to the world in the best-chosen language.”

The novel is now more widely appreciated, but many of its best writers over the years have remained in obscurity.

Women writers don’t seem to have fared as badly as women artists, but they haven’t gotten the recognition they should. Only four of the 26 writers in Harold Bloom’s much-read book The Western Canon are women (all white, too!) — not to be confused with Dana Schwartz’s The White Man’s Guide to White Male Writers of the Western Canon (which I haven’t read but looks entertaining). That’s better than the zero women H. W. Janson included in his History of Art, but it’s not good. Most of us know names like Jane Austen, the Brontes, George Eliot, Emily Dickinson, Virginia Woolf, Zora Neale Hurston, Flannery O’Connor, Edith Wharton, Willa Cather, and Toni Morrison. Yet so many others have been forgotten.

Certainly, some women never became writers because of the obstacles in their way. Virginia Woolf’s imaginary character Judith, Shakespeare’s sister, shares his talents but never fulfills them because of the life forced on the women of her day. (There has been speculation that Shakespeare was in fact a woman, but that’s also been refuted, with the acknowledgment that some doubts remain.)

Sadly, that’s not just an artifact of history. Women writers today may be less likely to get the attention of literary agents, as Catherine Nichols found in 2015 when she started submitting her novel using a man’s name and got much better results.

There’s no doubt that many women have been prevented from becoming writers because of society — and that others are still being thwarted. But as in the arts, and in just about every area of life, there have been more women writers than we might be aware of. They’ve just been hidden from view. It’s time that we start seeing them again.

Yes, I have issues with Women’s History Month — yet here I am writing about it. In case you missed them, the first posts in this series are here and here.

As always, a wonderful read. I just learned about Aphra Behn in a podcast I started listening to recently (Not what you thought you knew, season 1, episode 2)!