A million species on our planet face extinction, according to a 2019 U.N. report. Extinction rates are accelerating rapidly, and the World Wildlife Fund recently determined that since just 1970, wildlife populations on the Earth have declined by 69%.

These are overwhelming facts to face. Even if you don’t love wildlife, this should matter to you. Nature is not a nice-to-have. A decline like this affects all of us deeply. The loss of so many species severely degrades the ecosystems that sustain us.

I don’t need to tell you that we are all connected and that we humans rely on the complex web of life on our planet for our very existence. That’s a well-known fact.

So I’ll skip lamenting or lecturing and get right to the point: There’s something any of us with access to a small patch of land can do, right now. Yes, we need to change the systems that have led to this crazy situation. But you don’t have to wait for systemic change to take action now. And it might be simpler than you think.

Wildlife in the U.S.

On a recent walk in nature with my friend Leslie, a garden designer and author, she told me about the work of Doug Tallamy, a professor who’s spearheading a grassroots effort to increase wildlife habitat in the U.S. The wildlife he focuses on is insects, since they’re the foundation of the food chain as well as pollinators.

Habitat loss is one of the major culprits in wildlife decline. Despite our many national parks and undeveloped regions, Tallamy claims that only 5% of land in the lower 48 states is in “anything close to its pristine ecological state.”

East of the Mississippi, Tallamy says, 86% of land is privately owned, and most of that is used for growing food or for lawns, which are an ecological disaster. Across the U.S., about 60% of land is privately owned, with about 63% of that being used for farms or ranches.

That’s a lot of privately owned land. While this presents a problem for wildlife, it also provides an opportunity.

Surprising places to create wildlife habitats

Our national parks and forests are too small and isolated to create the wildlife habitat we need. So Tallamy’s idea, which he calls Homegrown National Park®, is to “extend national parks to our yards and communities” by restoring habitats where we live and work. The goal is to create new ecological networks populated with native plants, thereby regenerating biodiversity and ecosystem function.

Native plants are key to these ecological networks because they attract the insects that the rest of the food chain relies on. Some other plants can help, too, but you’ll get the best results with natives, because insects like caterpillars, which are a pillar of the food chain (sorry!) have evolved to eat and reproduce on those specific plants. Most birds rear their young on a diet that’s heavy on caterpillars.

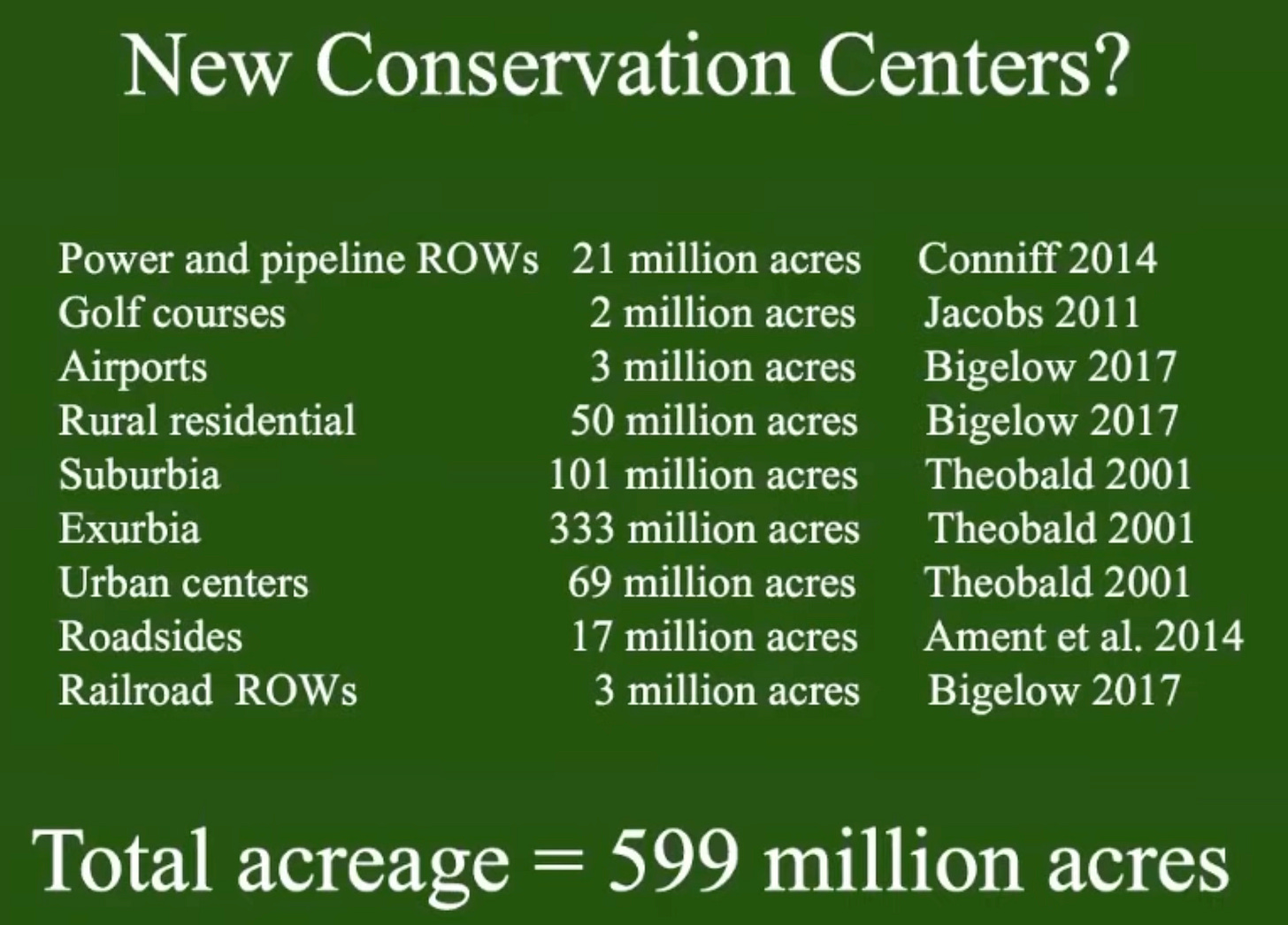

If you’re wondering where we’ll create all these ecological networks, Tallamy has plenty of examples of potential locations:

To give you an idea of the size of 599 million acres, it’s equivalent to adding up the states of California, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, New York, Oklahoma, Texas, Vermont, and Virginia.

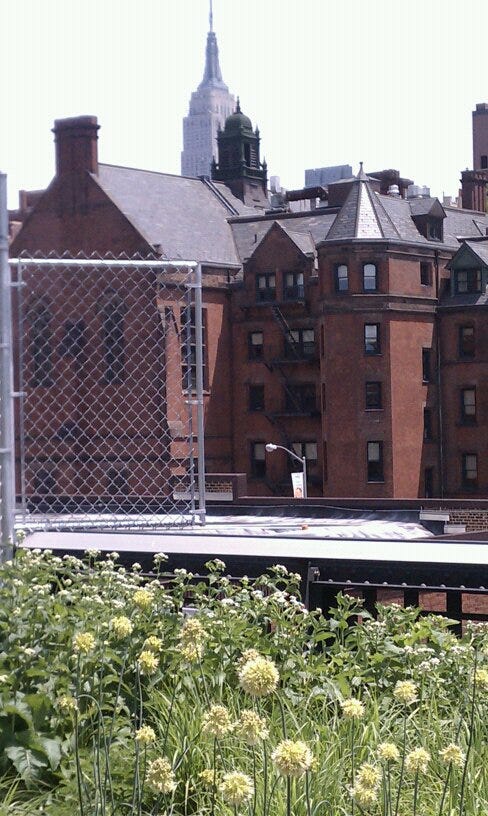

If you’re wondering how well it will work to create ecological networks in some of these locations, look no farther than the High Line in New York City. Planted with mostly native plants, the High Line is attracting plenty of insects, showing how doable this is even in the heart of the city.

A location you might not think of for habitat restoration is solar farms. Many solar developers are planting pollinator-friendly plants alongside solar panels. This helps with solar panel efficiency (because it keeps the panels cooler), plus of course attracting beneficial pollinators that can increase yields for local farms.

Small steps

Like growing food locally and producing energy locally, habitat restoration can be done at a very local level. We can each take small steps to help address the wildlife decline problem. As Tallamy says, “You don’t have to save biodiversity for a living, but you can help save it where you live.”

Anyone with a yard can start planting natives now. That doesn’t mean you must plant only natives; even a few can be a good start. Just avoid planting invasive species that will harm the natives.

You can start by shrinking your lawn. If you love having a lawn, don’t talk to me! I mean, that is to say, consider ceding just a portion of your lawn to create a wild space. Many cities will now pay you to convert your lawn, or part of it, to a more sustainable garden.

When you plant natives, focus on keystone plants, or the 5% of natives that Tallamy says account for 75% of caterpillar food. Oaks, for example, support more life forms than any other North American tree. To determine which natives to plant, use this handy Native Plant Finder, which ranks the native plants in your area. Check out Homegrown National Park for more tips and to get on their map when you plant your natives.

Don’t have a yard? See if you can influence your city to plant natives in a park or other green area; they may even let you adopt a park.

We can make a difference

Leslie has converted her garden in an urban neighborhood in Berkeley from a patch of dead grass to a woodland paradise.

She even planted (local, native) milkweed, with this beautiful result:

Monarchs are in danger of extinction, but they’ve recently experienced a bit of a rebound in the western U.S. — perhaps aided by efforts like Leslie’s.

Leslie’s urban garden is just one example of what we can do by taking some small, simple steps. You might be surprised at how quickly you can attract beneficial insects to your yard. And unlike many other actions we can take to improve our world, this one yields concrete results that you can see — and enjoy for years to come.

Do you have native plants in your garden? If not, are you inspired to plant some? Let me know in the comments!

I try to plant natives. Unfortunately, after more than 20 years, most of my gardening is battling invasives - buckthorn, purple loosestrife, reed canary grass, creeping charlie, bull thistle, invasive cattail and greater celandine. It's particularly difficult since our yard has a steep slope, so erosion is a major concern.

Lesley's yard is beautiful! What an inspiring read this week, thank you!