What They Didn't Tell Us About Medieval Women

And what the Middle Ages can teach us about our times

Much as I dislike Women’s History Month, I’ve devoted this one to focusing on a few aspects of women’s history, including art and writing. I could probably spend all year on this, writing about the lost history of women in various pursuits: science, medicine, law, politics, education, sports, etc., etc.

But that’s not how I want to spend my time. And by now, you’re probably thinking, we get it. Women have been doing stuff for as long as humans have been doing stuff, even when men (and the society at large) were trying to stop them from doing stuff. History, mostly written by men, has left out what women were doing and attributed the important and interesting stuff to men. We need to rewrite history to include everyone, and we still have a lot of work to do in this endeavor.

We get it.

So instead of delving into yet another specific area of achievement where women have been left out and misrepresented, I’m going to wrap up the month by looking at some ways history has distorted what we think of as both the role of women and also our very nature.

To start out, it’s important to note that history is not the straight line we envision it to be. I have a lot more reading to do on this, but so far I’m about a third of the way through the 526-page The Dawn of Everything, which makes a persuasive argument that societies didn’t evolve in some logical, predictable, progressive manner from hunter-gatherers to agriculture to modern civilization as we know it. Partly based on new evidence as archeological sites beyond Europe are studied more, partly based on accounts from various times that already existed but were largely ignored, the authors discuss the many forms of social organization that groups have experimented with — and often alternated among, even during the course of a year — throughout history.

The point is that where we are now is not inevitable, just as progress is not inevitable. Just as that’s true for most of the ways we organize and understand our society, it’s true for how we view women and the roles we play. We’ve made progress in some respects, and we’ve gone backwards in others. And we have the freedom to reimagine our society and all of our roles in it — if we choose to do it.

To really get this, it’s helpful to see how we got to where we are today. Looking at history from a new perspective shows us some surprising gaps. We can trace many of our views about women to the Middle Ages and the classical influences on that time; a closer look at the Middle Ages brings to light some new shit that’s not really new but that we’ve ignored for some time.

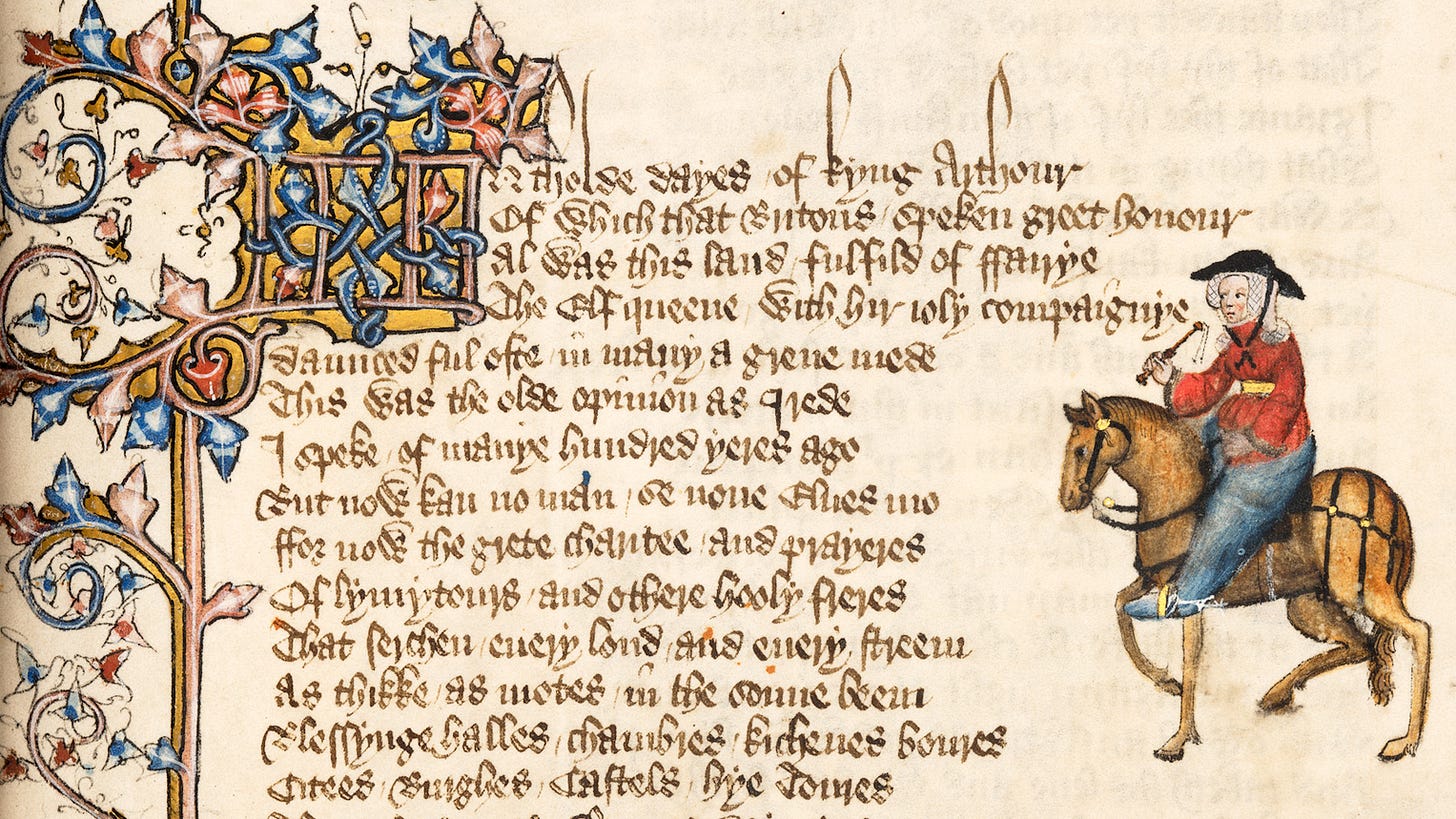

From The Once and Future Sex: Going Medieval on Women’s Roles in Society by Eleanor Janega, I’m learning that Christine de Pizan (who’s come up in a couple of my other posts this month) wasn’t the only woman doing stuff in the Middle Ages, though she was one of the more famous ones. It’s yet more evidence that the idea I grew up with — that women were just starting to do stuff and to take part in the workforce in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s — is a bunch of crap.

It turns out that most medieval women did additional work besides housekeeping and child-rearing, as has been the case throughout history — whether in the fields, which was the primary occupation for most people at the time, or in a number of trades. They could brew ale, weave textiles, and run shops and bathhouses; they could work as barbers, shipwrights, blacksmiths, court poets, and teachers. A common occupation for women of all classes was bookkeeping or accounting, with the result that math was thought of as an inferior pursuit to what educated men were doing — the more elevated philosophizing and such. Funny how women have somehow gotten worse at math as the status of math has risen.

Of course, as is still often the case now, women were also responsible for the housework and child-rearing. So they might come home after a long day of work to a scene like this:

“What kind of position is the wife in who when she comes in, hears her child screaming, sees the cat at the filch and the dog at the hide, her loaf burning on the hearth and her calf suckling, the pot boiling over into the fire — and her husband complaining.”

— Hali Meiðhad (Holy Maidenhood), 1190–1225

This sounds so much like what many women face today, perhaps minus the complaining husband (if he knows what’s good for him!). Even those of us without children know all about the mental load of running a household that women carry disproportionately. We’ve made some progress in this area, but not nearly enough; that could be a topic for many more posts.

Surely, though, we’ve made progress when it comes to women’s sexuality?

It depends on what you mean by progress.

In the Middle Ages, sex had a bad rap. It was a wild force to be tamed, conquered, and controlled — which men, apparently more self-disciplined, were considered to be good at, while women were not. In fact, people in the Middle Ages thought that women were obsessed with sex and insatiable; left to their own devices, they’d have sex as often as possible with whomever was capable of seducing them.

“Every woman in the world is likewise wanton, because no woman, no matter how famous and honored she is, will refuse her embraces to any man, even the most vile and abject, if she knows that he is good at the work of Venus; yet there is no man so good at the work that he can satisfy the desires of any woman you please in any way at all.”

— The Art of Courtly Love, c. 1184, by chaplain Andreas Capellanus

The idea that women were inherently more sexual than men was supported by the story of Eve in the Garden of Eden and by the classical authors medieval people were reading, like Aristotle, and like-minded contemporary ones, like Aquinas; those who couldn’t read were hearing their ideas in sermons and mystery plays. Women were seen as so sex-crazed that when they gathered together they might be accused of running brothels.

Fast-forward to present times, and our society has rather different views about sex. Now that it’s generally considered a positive thing — with some notable exceptions, of course — the current assumption is that women are less interested in it than men.

We’ve gone from Chaucers’s Wife of Bath, whom Janega notes “is a good businesswoman but is greedy and sex-crazed,” to what she calls the “incredibly modern” idea that women aren’t interested in sex. That’s brought us to Stephen Fry, a gay man who somehow considers himself an authority on women’s sexuality, making the extremely annoying (to say the least) comment that “If women liked sex as much as men, there would be straight cruising areas in the way there are gay cruising areas.” Here’s Janega’s great response (click to read the full thread on Twitter):

As misguided and absurd as Stephen Fry’s comment is, you know there are others out there thinking like him; the idea runs deep in our current culture. And yet, it wasn’t always like that.

So, there you have it, folks! Women used to be hard workers who were good at math and obsessed with sex, but sometime between the Middle Ages and modern times, they lost both their enjoyment of sex and their math abilities.

What’s stayed the same?

The common thread is clear, says Janega. In case you can’t access the full Twitter thread above: “The thing about women is that they are always wrong. It doesn’t matter what a society values — you can rest assured that we will consider that women do that thing incorrectly.”

It’s a sad but true assessment. But the gift she offers is a clearer picture of our past, which gives us this crucial lesson: Things haven’t always been one way or another, and there has been no logical progression from then to now. That opens up possibilities for making real change. It’s up to us to realize those possibilities.

Always interesting with something to learn! The "modern" idea that women aren’t interested in sex is countered by the idea that women are at fault when they are sexually assaulted because they've lured men in. I kinda think that the "sex crazed" accusation was more of the same -- men blaming women throughout history for their own lack of control. But I'm no historian, so you never know!

Fascinating post!